A cable stretching into the clouds beckoned me onto the red gondola headed 5,381 feet into the air. The cable car swung slightly as it rose up a steep incline to the top of Enalp in Wasserauen, Switzerland — the northernmost summit of the Appenzell Alps.

From the top, it felt like the roof of Switzerland, with blue lakes and mountain peaks visible as far as the eye could see. The panoramic view, with endless green hills of unspoiled natural beauty, seemed straight out of Heidi.

|

A short hike from the summit through some mountain caves led me to a restaurant clutching the sheer rock face of the mountain, with only a dirt path around the building separating it from the plummeting mountainside. The Wildkirchli restaurant seemed the perfect spot to pause and reflect on the impossible magnificent scenery all around.

When I crossed Switzerland by train last October to learn about the country’s far-reaching history and even further-reaching natural beauty, it looked like a post card everywhere I turned.

A Geneva melting pot

My tour started in the international city of Geneva, which retains its medieval footprint despite its role as a leader in the modern world.

“People from all over the world live here,” said Ursula Deim-Benninghoff, my Geneva tour guide. “A little more than 40 percent of the inhabitants are foreigners. It’s one of the most international cities in the world. Walk down the street and find any food you want.”

As I passed several international headquarters in a row, including the World Health Organization and the Red Cross, it became clear why so many non-Swiss live here. Geneva’s long tradition of foreigners populating the city started with religious refugees flocking to the city after the Reformation.

Cobblestone sidewalks in part of the city’s medieval section led me to the four-year-old International Museum of the Reformation, which explains the history and theology of the movement.

“The 16th-century movement called the Reformation tore Europe in half,” said Francoise Demole, vice president of the museum’s foundation. “Ever since Calvin moved here, Geneva has been a center of the Reformation and an international city.”

With its original 18th-century apartment design intact, the museum relates some of the Reformation ideas in the Theological Banquet exhibit, in which John Calvin argues predestination with other theologians at a dinner.

Other exhibits chronicle the lives of Calvin and Martin Luther, and depict the tense atmosphere of the Reformation, when Protestants hid their Bibles in fireplaces. An underground tunnel reveals the maze of archaeological ruins below St. Peter’s Cathedral.

Diem-Benninghoff helped me navigate the dimly lit archaeological site that features layers of ruins from a Roman villa to 11th-century Christian churches. The site remains amazingly well preserved, with a Roman well, a mosaic floor and bones from a Celtic grave.

“We bring children in here, and they say, ‘Oh, it’s just rocks,’ when they first come in,” said Diem-Benninghoff. “But by the time they leave, they say they want to be archaeologists.”

After leaving Geneva by train, I had to look up to see Lausanne, a historic city perched on a hill.

“This is our early-morning fitness training,” joked Lausanne tour guide Irene Abderhalden. “Everything in Lausanne is up and down.”

Lausanne’s pedestrian-only cobblestone streets, with shops, an open-air market and reproduced medieval street signs, stay well traveled by locals.

Abderhalden told stories of the city’s past as she led me to the 12th-century gothic Cathedral of Our Lady, whose dazzling rose window depicting a square inside a circle to symbolize eternity contains 78 original 13th-century stained-glass pieces.

Golden train tickets

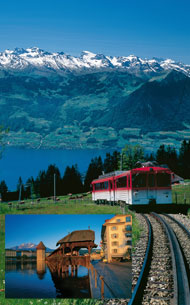

I boarded a gold-colored GoldenPass Panoramic Train with large windows stretching around the sides. The spacious train rounded the immense Alps beside aqua lakes, wooden chalets, and small farms with sheep and cows that somehow stayed upright on the nearly vertical mountains. As I studied the pristine landscape, a line of mist announced the coming of evening by casting a blue haze over the rocky peaks, like a creature swallowing the horizon.

That night I reached Paxmontana Hotel in the hamlet Flueli-Ranft, famous as the home of the hermit and saint Brother Klaus. The 1896 art nouveau hotel focuses on Brother Klaus’ theme of meditation by replacing televisions with binoculars, while a symphony of cowbells ringing from farms outside my window was like a lullaby.

|

Another train ride took me to Lucerne and its trademark Chapel Bridge and Water Tower. The 120 16th-century triangular paintings from the original medieval bridge still hang inside the replicated wooden bridge that was rebuilt after the original burned in 1993. Flowers line the sides of the bridge and window ledges all over the historic city.

“Welcome to the most beautiful town in Switzerland,” said Ursula Kottucz, my Lucerne tour guide as we reached one of several stone fountains. “Lucerne was founded exactly 830 years ago. Here, we are standing in front of the oldest fountain in Lucerne. It’s young though: It’s only 90 years old.”

Inside Lucerne’s 1666 baroque Jesuit church, I first glimpsed the joyful baroque style of colorful frescoes, intricate stucco and onion domes.

After hopping back on the train, I arrived in Einsiedeln, another city with a celebrated baroque church: the Abbey of Einsiedeln. A wandering hermit named Meinred reputedly founded the abbey in A.D. 828, when the region was nothing but a wooded wilderness. Today, people travel from all over the world to see its Black Madonna and the extensive library, which contains colorful handwritten texts from 861 on.

“We have 1,230 books made before people could print,” said Mona Zie, tour guide of Einsiedeln. “When you came here as a monk, you wrote the Bible for years and years. Everything was written by hand. They have books about things from politics to agriculture to religion.”

Books line the walls of the library, where some of the highlights, such as a 10th-century notebook and a 17th-century Bible translated into six languages, are placed in glass displays. Because the library holds so many earlier books, Zie allowed those in our group to take turns carefully holding the relatively new 17th-century Bible, which in any other library would have been for eyes only.

Once inside the abbey church, I heard the story of the Black Madonna, whose face has been darkened through years of candle smoke and incense. The figure stands inside the side Lady Chapel, with stucco surrounding the figure like a pillow of gold. The rest of the church shone with white walls and a ceiling covered in paintings, carvings, and gold and pink stucco.

“We are deep in the baroque style,” said Zie. “It’s all about harmony and illusion. You have to imagine people in the baroque time. The walls are always white, because we are here on earth. Only in heaven are the colors gold.”

|

A pioneer for peace

Known simply as Brother Klaus, he received his place of honor not from a rise in wealth, but by leaving his family to live as a hermit for prayerful meditation. Brother Klaus’ cramped wood

en cell still draws visitors to the hamlet Flueli-Ranft, where he lived most of his life. The Lower Ranft Chapel, with frescoes depicting the hermit and a reconstruction of the saint’s original home, also stands near the cell to demonstrate how he lived. “Nobles, viscounts, kings and pilgrims came to get advice on all kinds of issues, from political to social,” said Agnes Tallegger, Flueli-Ranft tour guide. “He [Klaus] thought he was too busy. Lucerne had to open a pilgrimage office.” How Klaus’ advice to Switzerland’s canton leaders convinced them against war still remains a mystery. “He believed the solution was to discuss, and not to fight,” said Tallegger. “That’s why he’s called ‘the peacemaker.’ And that’s also the position of Switzerland: to make peace.” |

Holy wars

Bells from 1772 rang out a deafening chorus while I toured St. Gallen Abbey, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site in St. Gallen. The city now peacefully runs a Catholic church and a Protestant church next door to one another, but remains of the wall that once divided the city by religion still stand along the edge of the abbey.

“It was difficult to live in this city in the 16th century, when half was Protestant and half was Catholic,” said Katalin Schwainger-Planta, tour guide at St. Gallen Abbey. “The monks began offering free drinks when the Protestant bells were ringing. This was the atmosphere in the middle of the 16th century.”

Fortunately, through the Reformation, a fire and the eventual dismantling of the abbey, the 106,000 priceless texts of the St. Gallen Abbey Library remained intact. Prayer books, vocabulary books, colorfully illuminated texts and a bill of sale for the abbey property, all written before 1000, fill the display cases inside the abbey library. The magnificent library room is a treasure in itself with burnished woodwork, curving balconies and ceiling frescoes that made everyone in our group gasp.

The connected 1755 St. Gallen Cathedral elegantly shows off more of the baroque style with stucco made to look like marble and one painting with a stucco leg coming out of the ceiling in a three-dimensional effect that my guide had to point out to me.

“The artists were clever,” said Schwainger-Planta. “They wanted people’s full attention. So to completely understand it [the painting] you have to look two or three times. It is

|

full of illusions.”

Because Switzerland contains four official languages in different parts of the country, I began my tour with French-speaking locals and ended it in German-speaking Zurich. Zurich not only features banks, endless shopping and the creamy Lindt Swiss chocolates, it also has a history of religious upheaval.

“Now we are in the medieval part of town, so no more paved streets, but cobblestone lanes,” said Ruth Rey, my Zurich tour guide. “Zurich has never been destroyed by war, fire or earthquake, which is why the medieval part of the city is as nice as it is.”

With the snow-capped Alps in the distance, I walked past former guild houses, old-fashioned grocery shops and several churches, including Fraumunster and Grossmunster, where Reformation leader Huldrych Zwingli preached reform. Evidence of Zwingli’s influence still exists at the gothic Grossmunster, with Zwingli’s Bible, original pulpit and the stripped interior of the church simplified to prevent decorations from distracting churchgoers.

After I bid good-bye to the beautiful Alps that had been my companion throughout the trip, performers playing alpenhorns resounded through the Zurich train station before a train whisked me away to the airport.

Switzerland Tourism

(800) 794-7795

www.MySwitzerland.com